Fastnet ’79: Safety Lessons We Still Use Today (and the night it all went wrong)

Some events become a permanent reference point. For UK sailing, the 1979 Fastnet Race is one of them. A severe August storm struck a fleet of offshore racers south of Ireland, leading to capsizes, abandonments, and a rescue effort on a scale never seen in peacetime British waters. The loss of life shook the sport and triggered a sweeping safety review. Forty-plus years later, many of the habits and rules we take for granted—storm sails, harnesses and tethers, sea-survival training, stability standards, better weather and comms—trace back to that night.

What happened in August 1979?

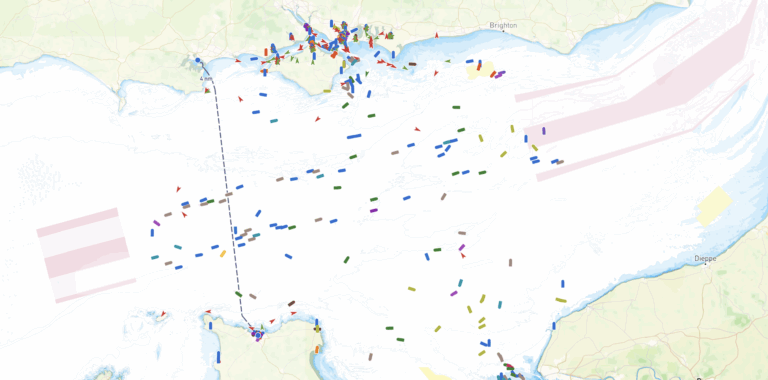

The Fastnet is a classic offshore course: traditionally Cowes → Fastnet Rock → Plymouth via the Isles of Scilly; since 2021 the modern edition finishes in France as Cowes → Fastnet Rock → Cherbourg-en-Cotentin. In 1979, a deepening low intensified faster than expected; by the night of 13–14 August the fleet ran into severe conditions south of Ireland. Contemporary accounts and the official inquiry describe winds reaching storm force with very large, confused seas. Out of roughly 303 starters, only 85 finished; five yachts sank, multiple boats were abandoned, and 15 sailors died. The rescue involved Royal Navy and RAF aircraft and ships, RNLI lifeboats and merchant vessels, with many thousands involved across a vast area.

Why it mattered: what the inquiry found

The 1979 Fastnet Race Inquiry looked at everything—weather, boat design and stability, watertight integrity, rig strength, liferafts, lifejackets, harnesses, watchkeeping, tactics, and radio use. Its recommendations pushed significant changes to Offshore Special Regulations and to the culture of offshore sailing: designers, skippers, organisers and rescue services all adapted. You can still see that lineage in today’s equipment lists, training requirements, and race management decisions.

Safety lessons that still apply to cruising sailors

1) Forecasts are guidance, not guarantees

Meteo models and dissemination are far better now, but the core lesson remains: treat forecasts as a range, not a promise. Read the synopsis, not just icons. For a practical refresher on pressure patterns and fronts, see Weather (Meteorology), and make a habit of comparing sources before deciding to go.

2) Set a go/no-go line—and stick to it

Define your personal limits for wind, wave height, crew fatigue and daylight. If the system is deepening or accelerating, you don’t need to “prove” anything. Write the rule into your Passage Planning & Making checklist with clear bail-outs and weather gates.

3) Stability and watertight integrity matter

After 1979, offshore rules tightened around stability, companionway design, washboards and hatch strength. For cruising skippers, the message is simple: keep washboards in and secured; shut/lock forehatches; maintain seals; don’t overload topsides; know how your boat behaves in quartering and beam seas. A tidy, watertight boat is a safer boat.

4) Harnesses, jackstays and tethers save lives

Plenty of 1979 MOBs happened because people were swept from deck. Today we treat clipping on as routine: rig continuous jackstays bow to stern; use crotch-strapped lifejackets with properly rated tethers; and agree “clip-on zones” (night, on deck forward of the cockpit, reefing, or when heel/sea state increases). Build it into your Keeping Safe at Sea crew brief.

5) Heavy-weather tactics: practise before you need them

The inquiry catalogued a spectrum of tactics used in 1979: running under storm canvas or bare poles, heaving-to, lying a-hull, towing warps, deploying drogues. There isn’t one “right” answer for every hull and sea state, but there is a wrong one: trying a method for the first time in a gale. Pick two tactics for your boat and rehearse them in a controlled breeze so everyone knows the drill.

6) Liferafts, grab-bags and decision-making

Liferafts and their lashings were a major focus of the report. Today’s takeaway: lash the raft so it’s accessible yet secure, fit a sharp knife nearby, and keep a grab-bag with water, meds, strobes/torches, spare handheld VHF and PLBs. Importantly, don’t rush to abandon ship. Step up into the raft only when the boat is no longer a safe platform.

7) Radios, DSC and distress calling

Radio discipline and coverage came under scrutiny in 1979. GMDSS/DSC and better aerials have transformed distress calling and coordination since. Make every crewmember comfortable placing a DSC distress and a spoken Mayday—scripts reduce panic. Use this quick refresher:

GMDSS VHF DSC Procedures for Small Boat Users

8) Casualty recovery from the water: why lift horizontally when you can

One practical legacy from Fastnet ’79 (and decades of SAR development since) is how we recover cold or exhausted people from the water. Hoisting a hypothermic casualty vertically can trigger dangerous “rescue collapse” as hydrostatic pressure is removed and cold, pooled blood returns to the core. Modern guidance therefore favours horizontal or semi-horizontal recovery whenever possible — using a stretcher, hypothermic/double strop, or a two-point hoist. If a quick vertical lift is unavoidable, keep it as gentle and short as practicable and lay the casualty flat immediately for monitoring and re-warming.

- Helicopter hoists: SAR crews routinely use double-strop/hypothermic strops or stretchers to keep the body aligned and supported in a horizontal attitude during the hoist.

- Boat recoveries: Aim for horizontal extraction (scoop boards, Jason’s cradle, slings) when the person is cold, semi-conscious, or immersed >30 minutes. Scramble nets/ladders are acceptable for short immersions in alert casualties, but watch for rapid cooling once out.

- On-deck care: Lay flat, insulate above/below, handle gently, and monitor airway, breathing, circulation. Expect afterdrop and keep talking to the casualty while you call for medical advice.

Tip: Add a short MOB/PIW recovery brief to your crew safety talk: who closes hatches, who handles the halyard to parbuckle, who manages comms, and where the thermal protection kit lives.

9) Training changes outcomes

Sea-survival and first-aid training expand your options under pressure. Drills build muscle memory: clipping on, heavy-weather reefing, heaving-to, MOB under power and sail, and DSC Mayday. Your future self will thank you for treating practice as non-negotiable.

10) Watch systems and fatigue

Several boats in 1979 became overwhelmed as fatigue set in. A realistic watch system (shorter stints when it’s rough), hot drinks, dry spares, early reefs, and strict cockpit tidy-ups prevent small slips turning into big ones. “Slow is pro” when the boat is lurching.

11) Debrief every rough passage

What worked? What didn’t? Did your plan match the sea state you found? Keep a notebook and refine your SOPs. The best skippers iterate.

A short history note (context for your crew)

The fleet left Cowes on Saturday 11 August 1979. As the low deepened, conditions escalated to storm force by the night of 13–14 August south of Ireland, with very large, confused seas. Of approximately 303 entries, only 85 finished. Five yachts sank, many were abandoned, and 15 competitors lost their lives. The response drew in Royal Navy and RAF units, RNLI lifeboats, merchant ships and fishing vessels—often described as one of Britain’s largest peacetime maritime rescue efforts. These events prompted the joint RYA–RORC Fastnet Inquiry, whose recommendations reshaped offshore safety standards. (Sources linked below.)

Practical prep you can do this week

- Open your Passage Planning & Making module and add a “heavy weather” pre-sail checklist.

- Revisit Weather (Meteorology). Compare the UK Inshore Waters bulletin with your favourite app before every passage.

- Run a 30-minute clip-on & heave-to drill at the mooring.

- Make a crew card for Mayday / Pan-Pan calls and stow it by the radio. Pin the Life-saving signals sheet by the nav table:

Life Saving Signals Table

Related RYA courses (overview & providers)

- RYA First Aid — course overview & providers

- Offshore Personal Survival (World Sailing/RYA) — overview & providers

Further reading & sources

- 1979 Fastnet Race Inquiry (full report, RYA–RORC)

- ECMWF re-forecast of the 1979 storm (how modern models would have warned earlier)

- Royal Navy 40th-anniversary piece (scale of the rescue, assets deployed)

- RNLI: Storm Force 10 — the Fastnet disaster

- RNLI: The Fastnet disaster — 40 years on

- RORC Centenary notes (1970–1980) — inquiry & offshore standards

- UK Chamber of Shipping: Recovery of Persons in Water (PIW) — small-vessel good practice

- Airmed & Rescue: Hoisting unconscious casualties — hypothermic/double strops

Enrol when you’re ready

- Start Day Skipper Theory online

- Take the VHF (SRC) online course

- Join the free Sailing Essentials course

Good seamanship is a thousand small, boring decisions that keep drama out of the cockpit. Learn the lessons in fair weather—so you don’t have to re-learn them in a storm.