Bottom-Up vs Top-Down: Pilotage Plans That Work

Making Pilotage Plans That Actually Work in the Cockpit

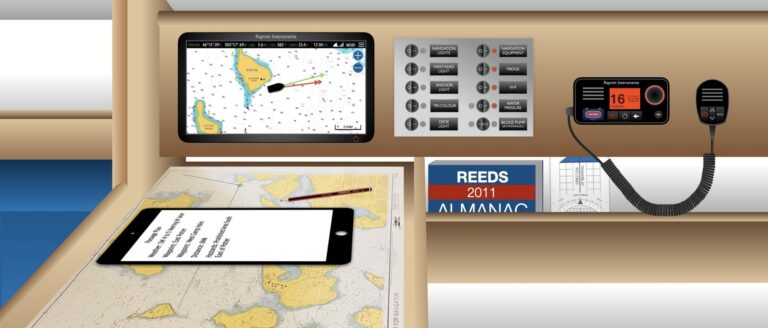

Over the past few months I’ve run a string of practical sessions with trainee skippers who did their theory elsewhere. The waters were straightforward, by day and by night, yet we hit the same snags again and again: plans that were either mini-essays (beautiful but unusable at the helm) or so thin that the skipper had to fall back to a phone or the plotter. On two occasions I slowed or stopped the boat so we could reset. None of this was about intelligence or motivation; it was about format. The plan in your hand must support execution in real conditions. That’s where the “bottom-up” and “top-down” debate matters.

The patterns I keep seeing

- The over-written plan.

Pages of notes, every buoy’s history, and a paragraph for each leg. Once the wind pipes up and the ferry appears, the skipper goes heads-down to find the next paragraph; the plotter starts doing the thinking, and situational awareness evaporates. - The skeleton plan.

A couple of headings and distances with “turn at red can”. No minimum depth, no clearing bearing, no abort option. When the mark isn’t where expected (tide, visibility, mis-ID), there’s nothing pre-decided to keep the boat safe while you figure it out. - The left/right flip.

Top-down lists that read nicely at the saloon table but flip port and starboard relative to the vessel once you’re on deck. At night it’s worse: “see a red light” without saying where relative to the bow invites mis-identification and premature turns.

Those experiences convinced me (again) that the cockpit doesn’t need more data; it needs clarity at a glance.

What the cockpit actually needs

Whatever layout you prefer, the content never changes. A cockpit-ready plan captures four essentials:

- Stages & Alterations — split the track at each change and write one-breath instructions.

- Headings & Distances — initial °M and nm for orientation and timing checks.

- Safety Limits — minimum depth, clearing bearings/no-go lines, clear abort/holding option.

- Recognition Cues — what you must see and where you expect to see it (relative to the vessel).

We park operational admin — VHF channels, reporting/calling points, places where permission to proceed is required (river crossings, locks, bridges), local speed/no-wash rules, berthing instructions — in a separate Comms, Permissions & Local Rules box so the stage lines stay clean.

The virtue of “bottom-up”

Our cockpit sheet is designed to be read from the bottom upwards as you progress. The magic is not that the next step always sits on the lowest line (it won’t, once you’ve ticked a few off). The win is spatial: a bottom-up layout naturally keeps notes on the correct side of the track from the helm’s perspective — port notes to the left of the line, starboard notes to the right. In the real world, that erases a lot of ambiguity.

- Left/right certainty. No mental gymnastics to remember which way the list maps to reality.

- Night pilotage clarity. Light characteristics (e.g., Fl.R(3) 5s) gain meaning when paired with where you expect to see them: “on starboard bow before alteration”.

- Tick-as-you-go. Check-boxes next to each stage make it obvious where you are in the sequence, even when distracted.

Caveats: some crews find the format unfamiliar at first; a thirty-second pre-brief solves that. And while the “rolling road” analogy is helpful, don’t force the idea that the next action is literally at the very bottom of the page — it isn’t!

The virtue of “top-down”

Top-down, numbered instructions with a thumbnail sketch are wonderfully familiar and excellent for briefing. They provide a narrative: 1, 2, 3… and can preserve your reasoning (why you’re doing A before B). For training, they’re useful because they show the decision chain: hazards, options considered, choice made.

Where skippers come unstuck is assuming the top-down list will run the cockpit as is. Two fixes make it work:

- Add explicit PORT/STARBOARD cues to every recognition line (“green conical to port abeam”) so the side never flips.

- Format for scanning: one action per line, generous spacing, and a clear way to mark the current step.

In other words, top-down is strong as a planning and briefing tool; to be cockpit-ready it needs a little more structure.

The hybrid that keeps boats safe (and calm)

What I teach is simple: use both. Create a passage plan for the big picture — weather and tide strategy, route and margins, waypoints and ETAs, contingencies. Then produce a cockpit-ready pilotage plan for the confined bits: the four essentials plus a separate Comms, Permissions & Local Rules box. The passage plan is top-down and narrative by nature; the cockpit sheet is bottom-up and spatial.

This split delivers the best of both worlds. The briefing is coherent. The execution is crisp. And you’re not writing a novel you can’t read in a breeze.

Day vs night: same logic, stronger discipline

By day, recognition cues tend to be shapes and contrasts: posts, piles, leading lines, a church spire in transit. The pitfalls I’ve seen are premature turns (no “seen before altering” rule) and corner-cutting where the plan lacked a clearing bearing or no-go line.

By night the discipline must be tighter. Cues become light characteristics and sectors; looms and background lighting can trick tired eyes. Two common errors from recent runs:

- “See a red light” without place. If you don’t say where relative to the bow and when along the leg you expect to see it, anything red can drag you off track.

- Using headings as truth. Headings are for orientation; tide and leeway mean the ground track will differ. Pair headings with cues and safety limits, not instead of them.

In both cases the bottom-up layout helps because it forces you to note the cue on the correct side of the line and to confirm it before the action. Slow the boat, stretch the spacing between actions at night, and make aborts easy to execute.

Real-world examples from recent students

- The river entrance that bent the brain. A trainee arrived with a tidy top-down list but no side cues. “Turn at red can” became “which red?” as background lights muddied the picture. A simple addition — “PHM on starboard bow before altering” — plus a clearing bearing would have prevented the wobble.

- The night approach with the wrong red. Another skipper wrote “expect red flashing 3” but didn’t say where or when. A hotel sign’s red flicker nearly got the nod. Rewriting as “Fl.R(3) 5s on starboard bow, seen before altering” and putting it on the right-hand side of the track cured it.

- The essay that stopped the boat. One plan read beautifully but demanded constant reading. When the helm asked for the next instruction the skipper had to scroll a phone. We paused, extracted four short stage lines with tick-boxes, and the stress disappeared.

Choosing your method (and making it bullet-proof)

- If you’re new to pilotage — or teaching it — build a bottom-up cockpit sheet and keep a top-down overview for your brief.

- If you love top-down, keep it — but bake in side cues and one line per action.

- Whatever you choose, capture the four essentials and keep Comms, Permissions & Local Rules separate so stage lines stay clean.

- Remember the cockpit plan is for the skipper/navigator to run the con and issue crisp, one-breath instructions; it isn’t a crew handout.

- Add tick-boxes. They’re not childish; they’re clarity.

The bottom line

There isn’t one “right” format. There is only the format that makes errors less likely for you. Over the past few months I’ve watched good people wrestle with plans that were either too dense to use or too thin to protect the boat. The fix wasn’t more information; it was better information, expressed the right way. Choose a method, keep the content consistent, and make the page mirror reality. Your future self — in a breeze, at night, with a ferry on the quarter — will thank you.